COCTEAU JEAN: (1889-1963)

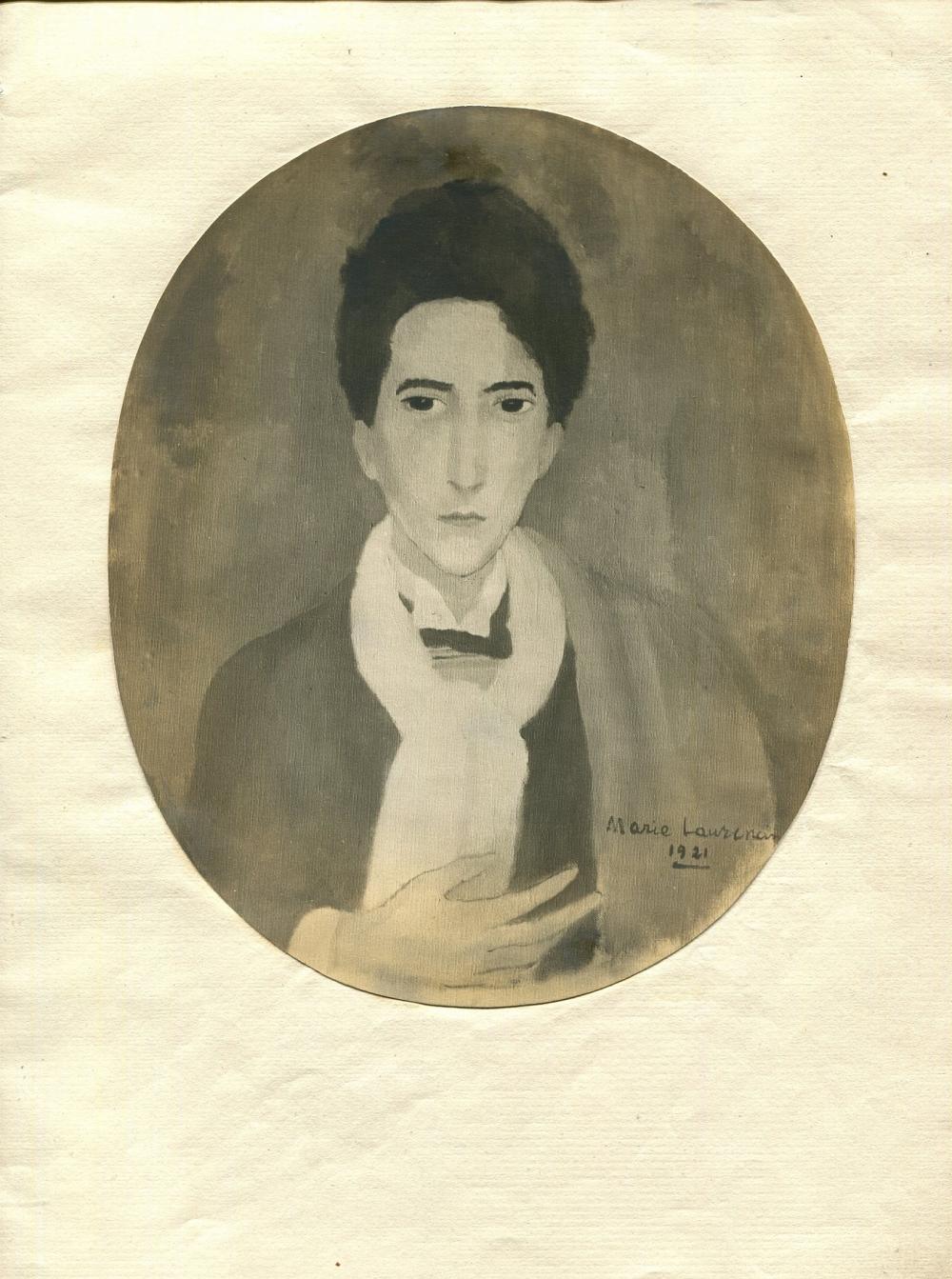

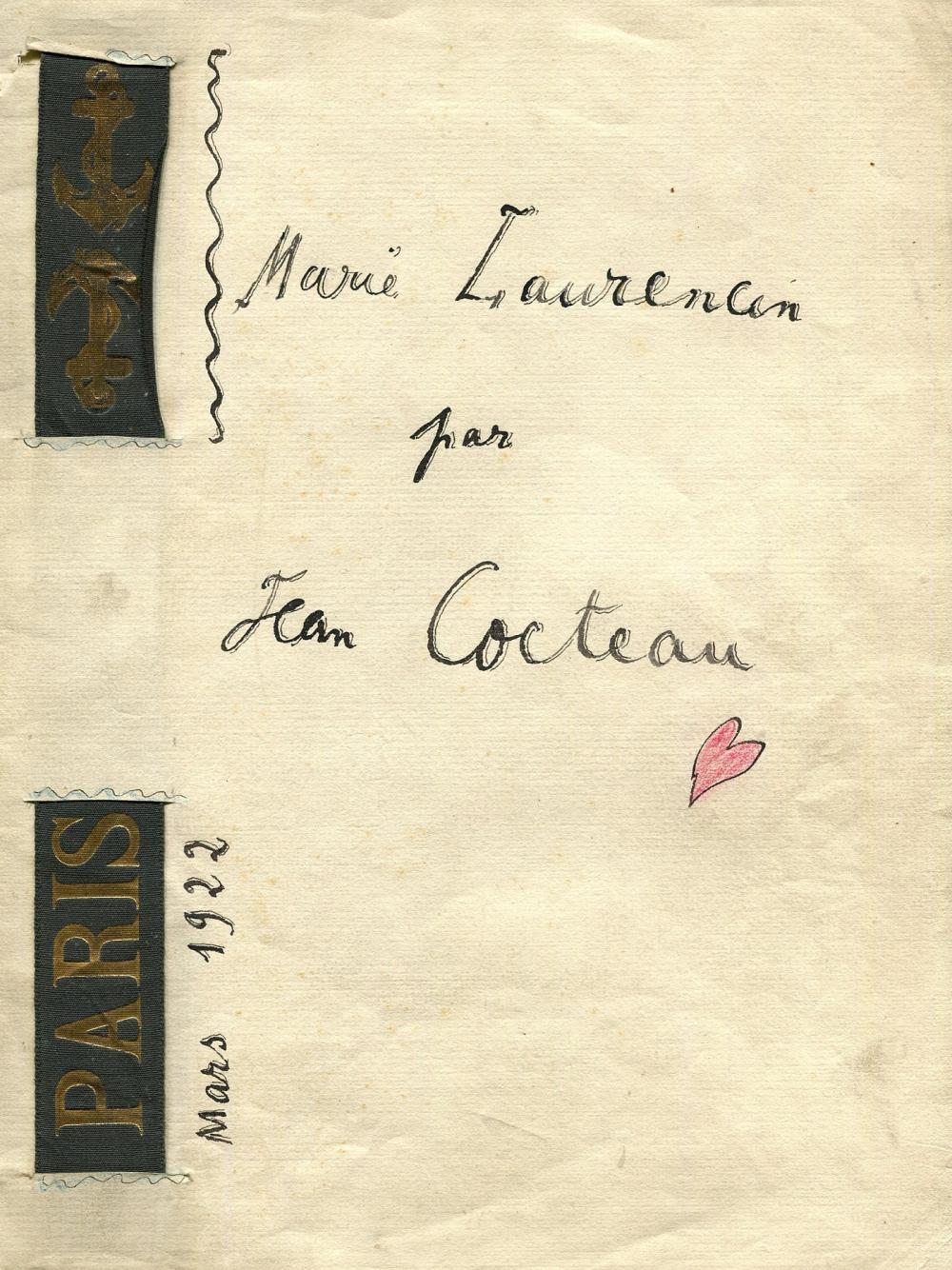

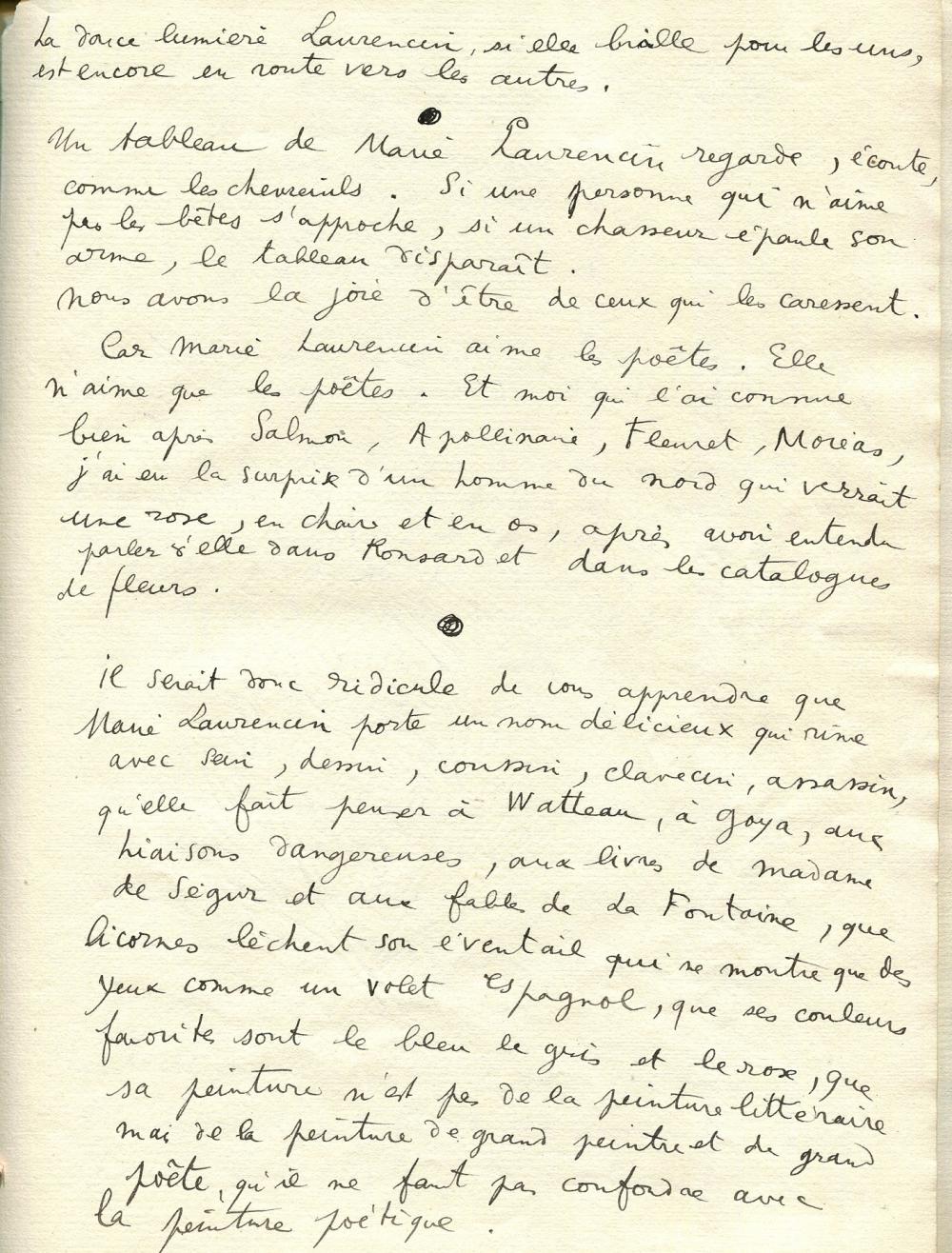

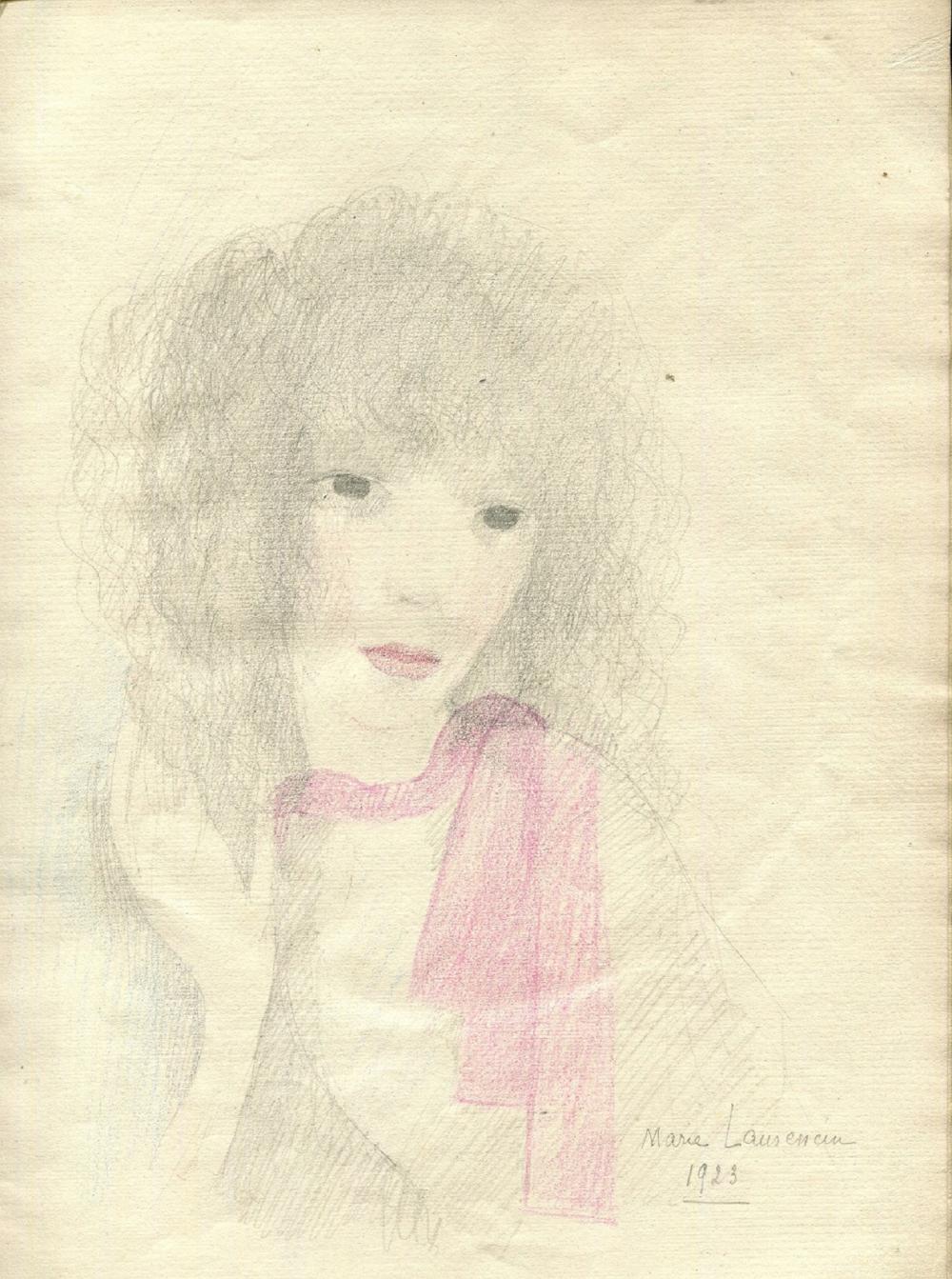

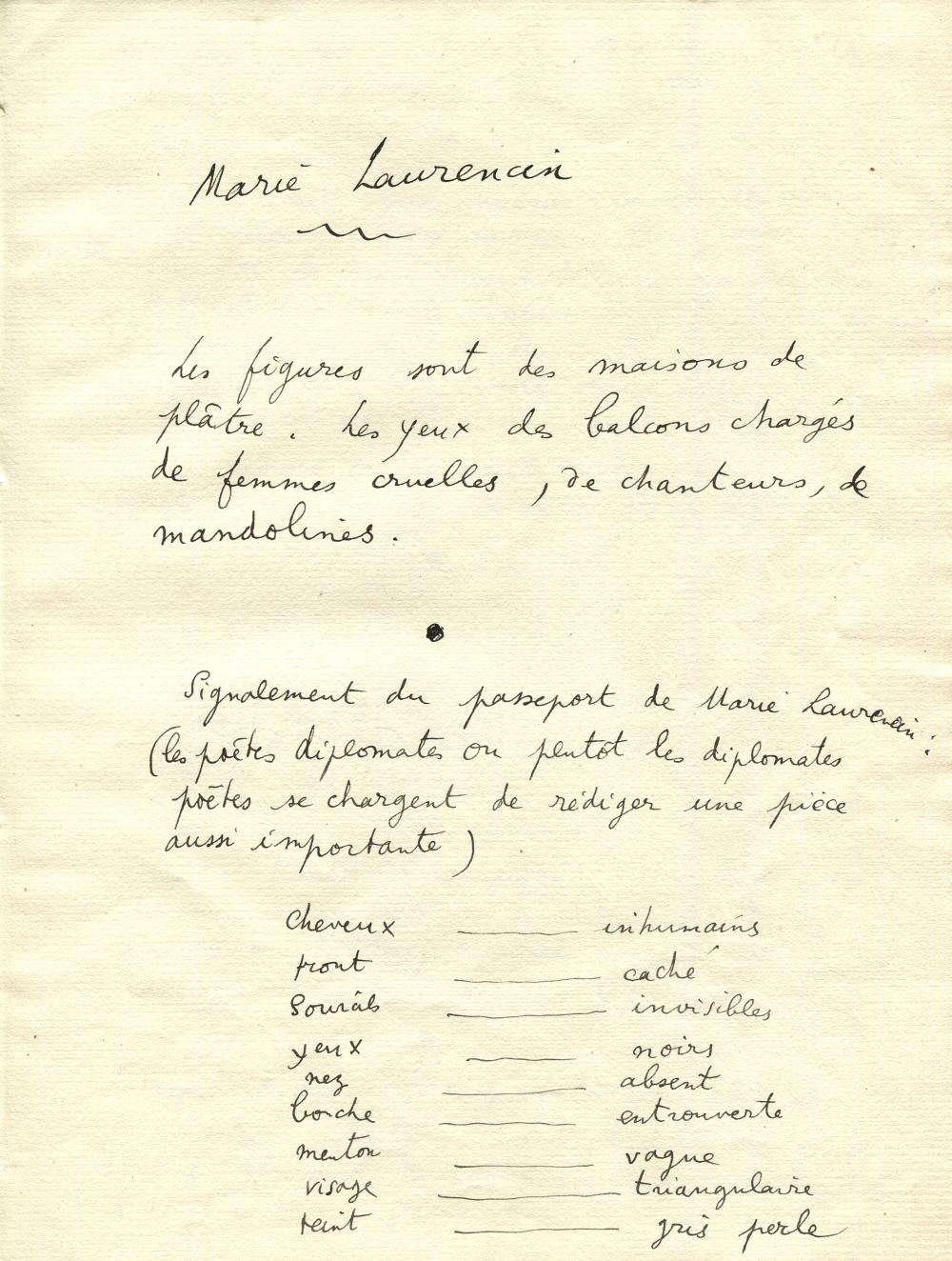

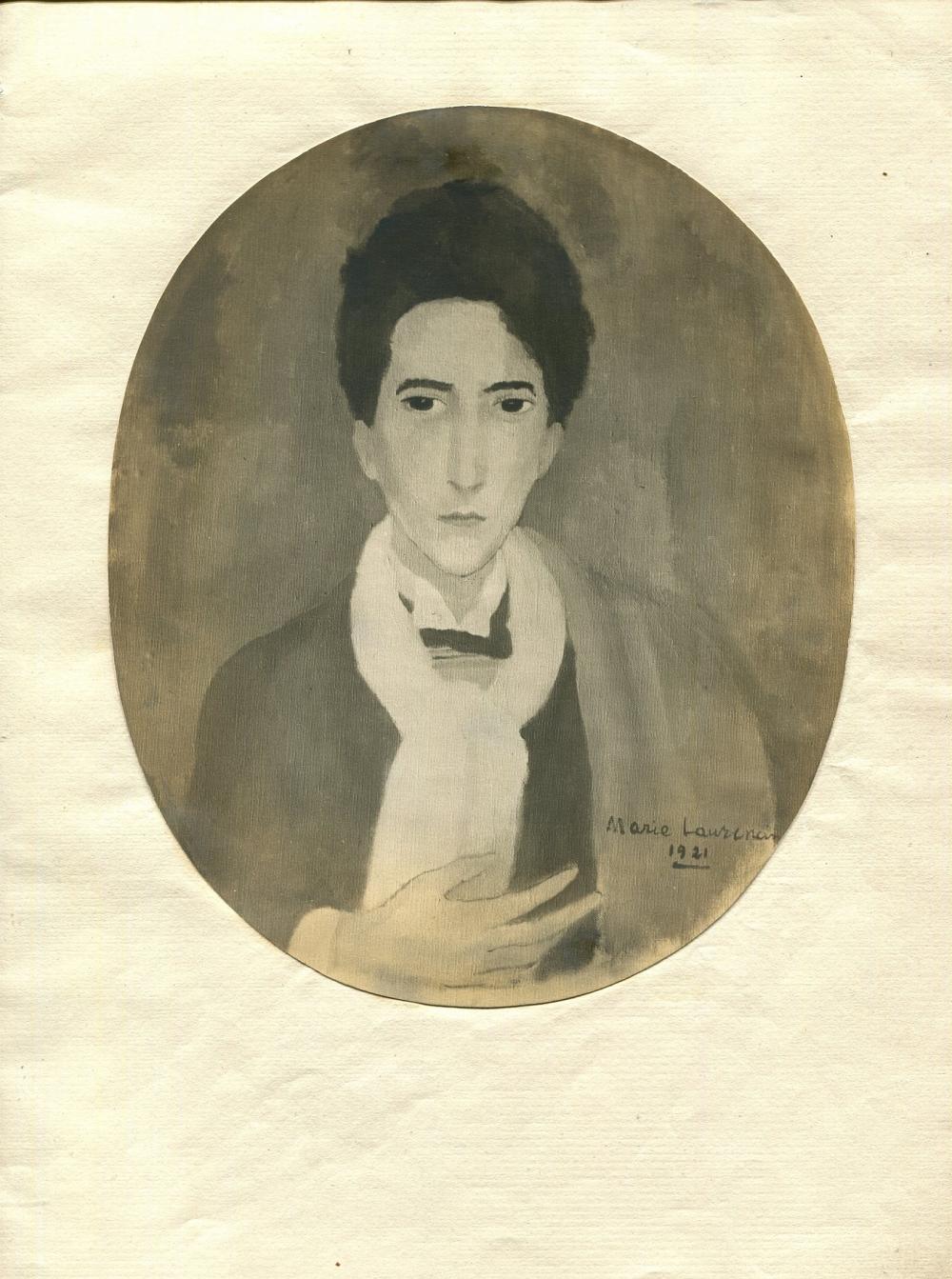

COCTEAU JEAN: (1889-1963) French poet, playwright, novelist, artist, filmmaker and critic. A remarkable autograph manuscript signed, Jean Cocteau, seven pages (rectos only), 4to, Paris, March 1922, in French. Cocteau’s manuscript is entitled Marie Laurencin, and represents a glowing appreciation of the French painter, commencing with a beautiful description of how Cocteau imagines her features would be recorded in her passport, noting her hair, black eyes, and pearl grey complexion, as well as several special features. ‘chevaux, colombes. eventails, plumes d'autruches….. yeux myopes’ (Translation: ‘horses, doves, fans, ostrich feathers….myopic eyes’, continuing ‘Mais elle ne veut pas qu'on dise qu'elle est myope. Elle trouve la myopie honteuse et le face a main la gene comme une bequille d'infirme. Pourtant il faudrait parler de ce nuage qui met les distances entre sa personne et le reste du monde, qui fait d'elle un aveugle et un caniche. Mais jamais on n'avait vu un aussi joli aveugle dirige par un caniche aussi savant’ (Translation: ‘But she doesn’t want people to say she’s short-sighted. She finds myopia shameful and face-to-hand discomfort like a cripple’s crutch. Yet we should talk about this cloud which puts distances between her person and the rest of the world, which makes her blind and a poodle. But we had never seen such a pretty blind man led by such a knowledgeable poodle’). Cocteau follows with a sestet – Une etoile d'amour, Une etoile d'ivresse, Les amants, les maitresses, Aiment la nuit et le jour, Un poete m'a dit qu'il etait une etoile, Ou l'on aime toujours. Translation: A star of love, A star of intoxication, Lovers, mistresses, Love night and day, A poet told me that there was a star, Where we always love And compares the stars to a calligram by Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘Sans doute il est trop tard pour parler encore d'elle serions nous tentes de dire, apris l'image que nous en donnent les poetes avec lesquels notre ame a toujours vecu. Jamais trop tard, il est vrai la douce lumiere Laurencin, si elle brille pour les uns est encore en route vers les autres’ (Translation: ‘No doubt it is too late to talk about her again, we would be tempted to say, after the image that the poets with whom our soul has always lived give us. Never too late, it is true the gentle light Laurencin, if it shines for some and is still on its way to others’). Cocteau then writes of Laurencin’s paintings. ‘Un tableau de Marie Laurencin regarde, ecoute, comme les chevreuils. Si une personne qui n'aime pas les betes s'approche, si un chasseur e'paule son arme, le tableau disparait. Nous avons la joie d'etre de ceux qui les caressent. Car Marie Laurencin aime les poetes. Elle n'aime que les poetes. Et moi qui l'ai connue bien apres Salmon, Apollinaire, Fleuret, Moreas. j'ai eu la surprise d'un homme du nord qui verrait une rose, en chair et en os, apres avoir entendu parler d'elle dans Ronsard et dans les catalogues de fleurs. Il serait donc ridicule de vous apprendre que Marie Laurencin porte un nom delicieux qui rime avec sein, dessin, coussin, clavecin, assassin; qu'elle fait penser a Watteau, a Goya, aux liaisons dangereuses, aux livres de Madame de Segur et aux fables de la Fontaine, que licornes lechent son eventail qui ne montre que des yeux comme un volet espagnol, que ses couleurs favorites sont le bleu le gris et le rose, que sa peinture n'est pas de la peinture litteraire mais de la peinture de grand peintre et de grand poete, qu'il ne faut pas confondre avec la peinture poetique. Du reste, Marie Laurencin est un poete. Ecoutez plutot: Roi d'Espagne prenez votre manteau, Et un couteau, Au jardin zoologique, Il ya a un tigre paralytique, mais royal, et le regarder fait mal. Vous retrouverez dans cette petite piece ecrite pendant la guerre a Madrid, l'intonation d'une aristocrate’ (Translation: ‘A painting by Marie Laurencin looks, listens, like deer. If a person who does not like animals approaches, if a hunter shoulders his weapon, the picture disappears. We have the joy of being among those who caress them. Because Marie Laurencin loves poets. She only likes poets. And I know her well after Salmon, Apollinaire, Fleuret, Moreas. I had the surprise of a man from the north who would see a rose, in the flesh, after having heard about it in Ronsard and in flower catalogues. It would therefore be ridiculous to tell you that Marie Laurencin has a delicious name that rhymes with sein, dessin, coussin, clavecin, assassin; that she makes us think of Watteau, of Goya, of dangerous liaisons, of the books of Madame de Segur and the fables of La Fontaine, that unicorns lick her fan which only shows eyes like a Spanish shutter, that her favourite colours are the blue, grey and pink, that her painting is not literary painting, but the painting of a great painter and a great poet, which should not be confused with poetic painting. Besides, Marie Laurencin is a poet. Listen instead: King of Spain take your coat, and a knife. In the zoological garden, there is a paralytic tiger, but royal, and looking at it hurts. You will find in this little piece written during the war in Madrid, the intonation of an aristocrat’). Cocteau also makes reference to the paintings of Picasso, ‘La toile, en apparence, la plus hautaine de Picasso met en branle nos curiosites. Nous cherchons quels objets la motivent. Nous y entrons. Nous collaborons. Peu a peu son univers commande. Nous admettons qu'il reorganise la notre. Alors, devenus familiers de son oeuvre, nous ne sommes plus timides. Mais ici nous voila genes comme par l'ooeil d'un chien qui nous regarde, comme par une conversation avec un enfant ou avec une reine. Le privilige qui nous vaut de ne pas mettre l'animal en fuite, de ne pas faire crier l'enfant, d'etre admis en presence auguste, ne brise pas la glace. Peut-etre que tous ces personnages de conte de fees n'attendent qu'un geste irrespectueux pour sortir du charme. Ils peuvent attendre: nul ne l'ose’ (Translation: ‘The painting, apparently Picasso’s most haughty, sets our curiosities in motion. We look for what objects motivate him. We enter it. We collaborate. Little by little his world takes control. We admit that he reorganises ours. So, having become familiar with his work, we are no longer shy. But here we find ourselves embarrassed as by the eye of a dog looking at us, as by a conversation with a child or with a queen. The privilege which gives us not to put the animal to flight, not to make the child scream, to be admitted into the august presence, does not break the ice. Maybe all these fairy tale characters are just waiting for one disrespectful gesture to break the spell. They can wait: no one dares’). Cocteau concludes by recounting the circumstances when Laurencin painted his portrait, ‘Maintenant, je vais vous raconter comment Marie Laurencin peignait mon portrait......C'est le genre des oiseaux qui nidifient. De temps en temps ils transportent une brindille. Marie Laurencin chante. Elle se leve. Elle me montre un exercice de gymnastique. Elle tourne dans la chambre. Elle cherche de l'essence. Elle ne trouve pas ses tubes….. elle essaye une robe, elle ecrit une lettre et l'attache du cou d'un pigeon voyageur. Elle cherche un numero de telephone…….Le nid est fait. Le tour est joue. Ou se trouve en presence d'une oeuvre forte, grave, d'un equilibre et d'une poesie deconcertants’ (Translation: ‘Now I am going to tell you how Marie Laurencin painted my portrait…..It’s the typed of birds that nest. From time to time they carry a twig. Marie Laurencin sings. She gets up. She shows me a gymnastics exercise. She walks around the room. She’s looking for gas. She can’t find her hits…..she tries on a dress, she writes a letter and ties it to the neck of a carrier pigeon. She is looking for a telephone number…….The nest is made. That’s it. Where we find ourselves in the presence of a strong, serious work, of disconcerting balance and poetry’). The manuscript is loosely bound in the original paper wrappers, with Cocteau’s title to the front, ‘Marie Laurencin par Jean Cocteau’, also adding a small drawing of a pink heart beneath his name. Also included within the manuscript are two frontispiece illustrations, the first an oval monochrome photograph by Man Ray of Marie Laurencin’s 1921 portrait of Cocteau, the silver gelatin print measuring 19.5 x 16 cm, and the second a charming self-portrait by Laurencin, executed in pencil and showing her in a pensive head and shoulders pose, with a pink scarf and matching lipstick. Signed (‘Marie Laurencin’) in pencil at the foot of the portrait and dated 1923 in her hand. A wonderful manuscript, enhanced by Laurencin’s self-portrait and Man Ray’s photograph. Some light overall age wear and a few small areas of paper loss to the upper left corners of some pages, otherwise VG Marie Laurencin (1883-1956) French painter, an important figure in the Parisian avant-garde as a member of the Cubists associated with the Section d’Or.

- The cost is converted to USD at the rate of 1 EUR = 1.093 USD on 2023-11-30.

-

Sign in to view

Lot number

-

Sign in to view

Estimate

-

2023-11-30

Sale date

-

Sign in to view

Realised price

-

Sign in to view

Opening price

-

Sign in to view

House name

-

Sign in to view

Auction sale name

-

Sign in to view

Country

-

Categories

Sign in to view -

Tags

Sign in to view