Groups and Single Decorations for Gallantry

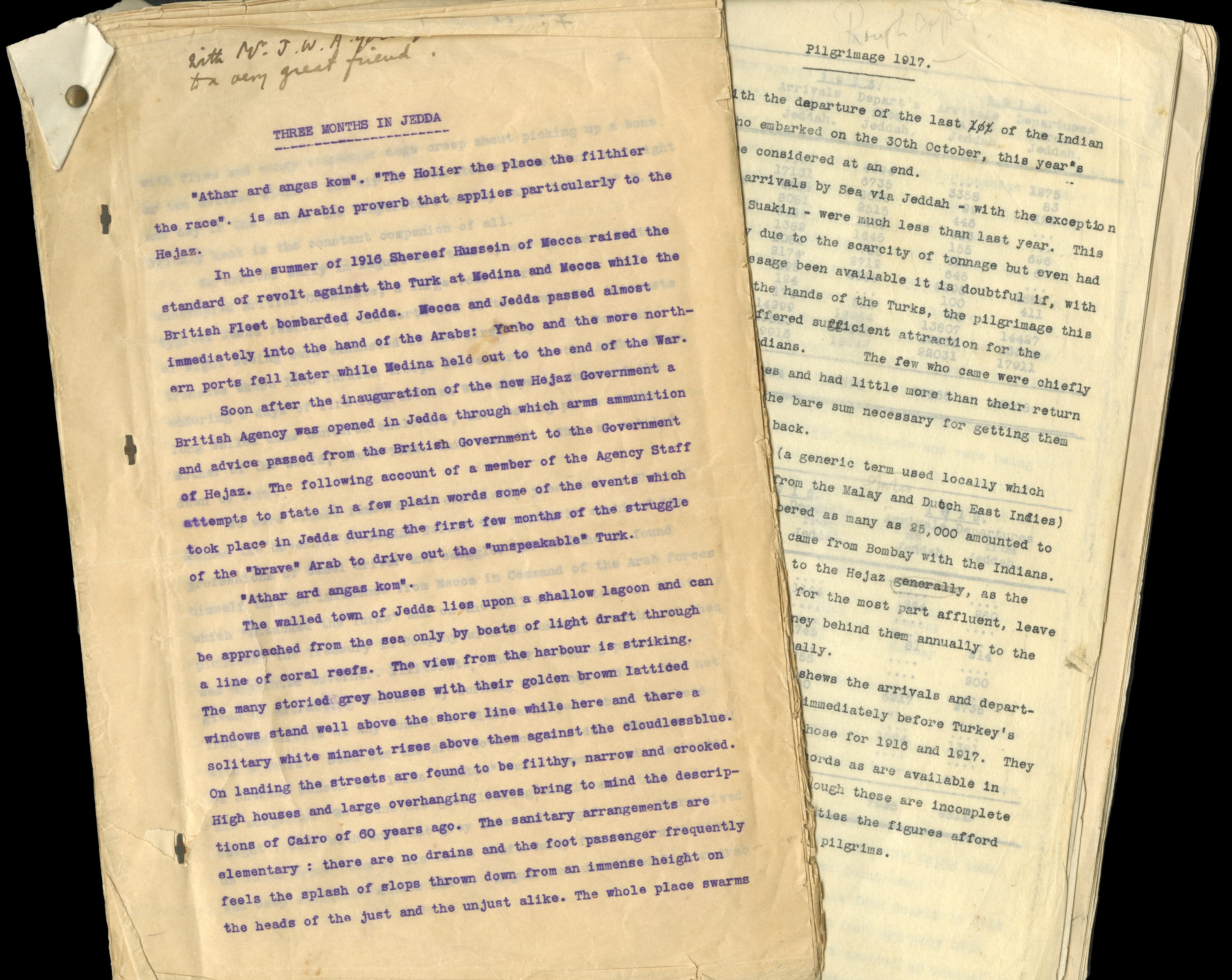

A most unusual and rare O.B.E. group of five awarded to Captain W. P. ‘Cocky’ Cochrane, a ‘Special List’ officer who served under Colonel Cyril Wilson, the British Representative at the Jeddah Consulate; operating under the auspices of the Arab Bureau at Cairo, the Jeddah Consulate was a vitally important hub of the Arab revolt and without the quiet diplomacy and intelligence work of Wilson and his small team the revolt would have collapsed and the world would never have heard of “Lawrence of Arabia” The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, O.B.E. (Military) Officer’s 1st type breast badge, silver-gilt, hallmarks for London 1919, in its Garrard & Co case of issue; British War and Victory Medals, with loose M.I.D. oak leaves (Capt. W. P. Cochrane.); Egypt, Kingdom, Order of the Nile, 4th Class breast badge, silver, silver-gilt and enamels, in its J. Lattes, Cairo case of issue; Hejaz, Kingdom, Order of El Nahda, a rare 1st type 3rd Class neck badge in silver, gold and enamels, complete with original plaited neck cord in its original case of issue, together with full-size ribbon pin bar, some minor enamel chips to the last, otherwise extremely fine and rare (5) £3,000-£4,000 --- O.B.E. (Military) London Gazette 3 June 1919: ‘For services rendered during the war.’ M.B.E. (Military) London Gazette 18 November 1918: ‘For distinguished service in connection with military operations in Egypt.’ M.I.D. London Gazette 17 September 1917, 7 October 1918 [Egypt], and 24 March 1919 [Mesopotamia]. Order of the Nile London Gazette 4 April 1918. William Percy Cochrane, born in Armagh in 1878, worked as a shipping agent for the firm of Gellatly, Hankey & Co., of Khartoum, and had worked in Jeddah before the war. August 1916 found Captain ‘Cocky’ Cochrane aboard H.M.S. Fox, anchored off Jeddah, accompanied by Colonel Cyril Wilson and Captain John W. A. Young. Wilson and his two junior officers had spent over two weeks in the cramped quarters of the warship, in their shirt sleeves in the punishing damp summer heat of the Red Sea, sending and deciphering secret coded telegrams, whilst awaiting more favourable conditions that would allow them to be landed by launch at Jeddah. Wilson had been appointed the British Representative at the Jeddah Consulate and, on 15 August 1916, the three officers landed from H.M.S. Fox to take up their appointments at the Consulate. In his memoir, A Little to the East: Experiences of an Anglo-Egyptian Official 1899-1925, Captain John W. A. Young who, arriving at Jeddah in H.M.S. Hardinge in July 1916, “reported to Colonel Wilson, whom I found together with Cochrane sitting in their shirt sleeves in sweltering heat deciphering code telegrams on board the cruiser H.M.S. Fox... it was not until a few days after our arrival that the British Consulate could be made ready for our accommodation.” A section of Sudanese policemen in due course came to the Consulate to guard them and to provide protection in the early months when the British ventured outside the town walls. Young wrote of Jeddah, “There was something about this town which hung heavy on the soul. We all felt it... Cochrane who already knew Jeddah well as a representative of the firm Gellatly Hankey and had lived above their offices there for months at a time, was from the beginning an invaluable foundation on which to build the administration of the Agency, a rock of sound common sense and a bastion of defence against Ruhi’s inaccurate gossip.” Ruhi was a diminutive Persian Bahai, officially interpreter to Colonel Wilson and unofficially an intelligence agent run by Ronald Storrs, Oriental Secretary to the British High Commission in Cairo. “More than once Cochrane and I [Young] were invited on board the flag ship Euryalus as the guests of the Commander in Chief, Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, and it was well worth the exposure to the midday heat in Gellatly Hankey’s somewhat smelly launch to enjoy his generous hospitality.” Young continues [in early 1917] “we laid out a golf course... while Cochrane and I procured horses on which I used to ride out into the desert to the limit of safety, about three miles beyond the town. But at the commencement political correspondence, Consular questions (settled chiefly by Cochrane), distribution of the monthly supply of gold, assistance to Said Pasha Ali in landing equipment for his Egyptian troops, coding and de-coding cypher telegrams kept us fully occupied.” T. E. Lawrence wrote to Young in 1921 and praised the work of the British Agency at Jeddah: “It was a jolly good improvisation and never broke down under stress. Cochrane and that Gyppy officer and old C.E. (Colonel C. E. Wilson), and Ruhi who brought us all those stories.” The Arab revolt had unofficially begun on 5 June 1916, and Wilson, whose official title was the harmless-sounding ‘pilgrimage officer’, well knew that a disrupted Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca could deal a fatal blow to the revolt. The Turks wanted to break out of Medina and recapture Mecca and Jeddah before the pilgrimage began, at a stroke crushing the revolt. Thus, while Lawrence and other British, Arab, and French officers were blowing up the Hejaz Railway, a forgotten band of British officers at Jeddah, far from the desert campaign, carried out vitally important diplomatic and intelligence work that prevented the revolt from collapse. This untold story is revealed by Philip Walker in his 2018 book ‘Behind the Lawrence Legend - The forgotten Few Who Shaped the Arab Revolt’. The story centres on Colonel Cyril Edward Wilson, the British Representative at the Jeddah Consulate. Wilson was a dependable officer of the old school—the antithesis of the brilliant and mercurial Lawrence. But his strong relationship with Sharif Hussein of Mecca, the leader of the revolt, drew this suspicious and controlling man back from the brink of despair, suicide, and the abandonment of the revolt. Wilson’s undervalued influence over Hussein during critical phases of the revolt was at least as important as the well-known influence of Lawrence over Emir Feisal, Hussein’s son. Wilson’s core team included the ‘unflappable’ Cochrane whose ‘careful preparations and the neutralising of dangerous plotters gave the great event [the Hajj] a favourable wind.’ Cochrane was largely responsible for the success of the Hajj Pilgrimages of 1916, 1917 and 1918. The compelling story of Wilson and his close-knit band points to an inescapable conclusion: the Jeddah Consulate was a vitally important hub of the revolt whose influence has been considerably undervalued. The military campaign in the desert was important, but Jeddah—with its artery to Mecca and Sharif Hussein—was the beating heart of the revolt, whose irregular rhythm needed the vital interventions of Wilson and his team. Without their quiet diplomacy and intelligence work, the revolt would have collapsed and the world would never have heard of “Lawrence of Arabia”. Cyril Wilson was the outstanding forgotten shaper and sustainer of the revolt. Near the end of Wilson’s life, General Reginald Wingate wrote to him praising his indispensable role and his “great work” in the Arab Revolt, without which, he said, it could never have succeeded. Wilson and his circle deserve to be commemorated, a century after their vital work fell through the cracks of history. It is not unreasonable to believe that Lawrence—complex and unfathomable as he was—would have acknowledged that this was so. Captain William Cochrane’s services in these...

- The cost is converted to USD at the rate of 1 GBP = 1.322025 USD on 2021-12-08.

-

Sign in to view

Lot number

-

Sign in to view

Estimate

-

2021-12-08

Sale date

-

Sign in to view

Realised price

-

Sign in to view

Opening price

-

Sign in to view

House name

-

Sign in to view

Auction sale name

-

Sign in to view

Country

-

Categories

Sign in to view -

Tags

Sign in to view